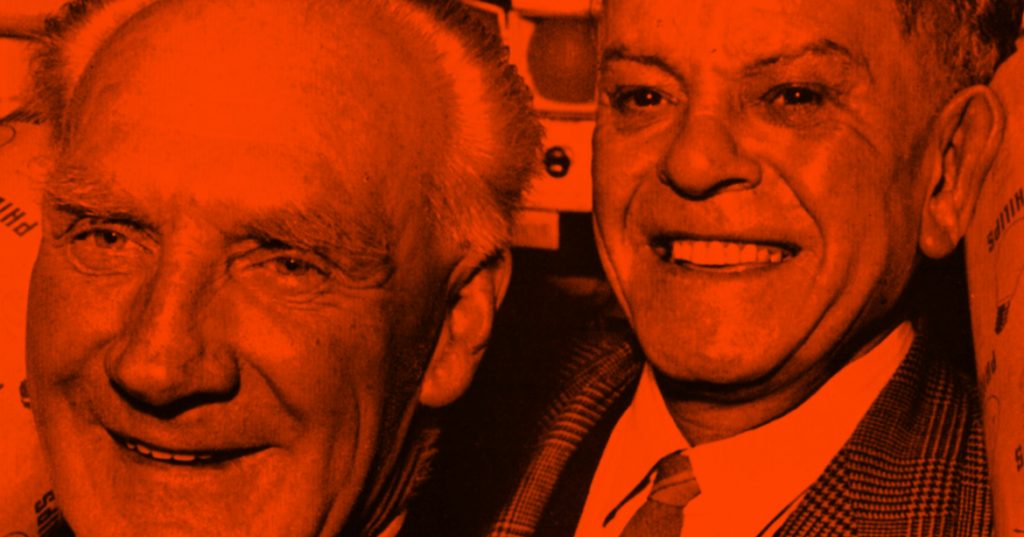

Feature billing for a pair of Bills

Bill Shaw and Bill Farrell, two of the men who keep Television House running

Bill was young and like many young men he had a keen sense of adventure; a desire to travel. Northern Ireland where he was born and brought up at the beginning of this century held few attractions for him. His Irish father and Scottish mother had not stood in the way of his elder brother when similar thoughts had passed through his mind … when, like many others at that time, his hopes had focused on a new land with new chances – Canada.

And so Bill’s brother sailed away. Bill was not long in joining him in Canada. There he soon found work. First he helped to make chocolate sweets. Then he worked in a Toronto biscuit factory. Bill might have become a prosperous Canadian but in Europe at that time factories in Germany were turning out arms not biscuits.

German troops were marching. War was declared and Bill, like many others who had sought fresh chances in new lands, decided that patriotism was a call he had to answer. He threw up his job, returned to England and volunteered. His brother clung to their newly-found country but also answered the call. He joined the Canadian Ambulance Service.

Soon, by some strange coincidence, the two brothers found themselves near to each other again in France. Bill, instead of packing biscuits into boxes, spent his time packing shells into gun barrels on the Somme not far from Ypres.

Five 100-lb shells screamed off towards the German lines a minute. The Germans replied and instead of 10 men manning each gun there were, more often than not, only four. But still the guns were fired. And still the German shells burst around them. Twice Bill had to be sent home with shell-shock. Twice he went back.

Then an offensive started against the Italians. They retreated and Bill was sent with the 29th Division in a bid to stop the advance. He helped to see that a fair proportion of shells were sent in the right direction before he, too, was injured. Ironically it was not a piece of shrapnel which pierced his leg, nor a stray bullet. A gun fell from its carriage on to him. And that was Blighty and the end of the war for Bill. Like thousands of others he had done his bit.

And so, in 1918, he was demobbed. Canada was a long way away. Bill’s brother went back. But perhaps the shellshock, the dreary days of hospital, had blunted Bill’s enthusiasm for a new country and a new life. Like thousands of others he did not find the transition from the Army to civilian life an easy one. He rejoined the Army.

As an experienced gunner they sent him to Shoeburyness, the Royal Artillery experimental depot. They made him a wine waiter to the 150 officers. He learnt a lot about wine and served many V.I.P.s when they came to see new weapons tested.

And there he met the girl who was to become his wife. She was governess to an Army officer’s children. In her younger days she had been an actress, once appearing as the principal boy in a Leeds pantomime. After their marriage Bill decided to leave the Army. They moved to Southend and Bill became a traveller to a firm which made umbrellas and walking-sticks. He tramped around Westcliff and Southend seeking orders. But his firm was a small one and not very prosperous. One morning Bill found himself out of a job. Luck was with him, however, for a dockers’ strike was on.

The same afternoon he was back in a job – working on the lighters unloading cargo from liners anchored oft Southend.

But that did not last long and soon Bill found new work – doing a milk round in Camden Town. Times were bad. He was forced to sack the boy who helped him. The boy retaliated by stealing the milk which Bill had left on the doorsteps. His pony had a long journey each day and dashed for his stable as soon as the last milk had been delivered. Perhaps there is a, by now, elderly policeman who remembers that pony’s attempt to knock him down in Trafalgar Square.

Bill began to prosper by taking over poor milk rounds, working them up into good ones and selling them. He soon knew Brixton, Victoria and Pimlico extremely well. Then he decided to stay put for a while and took over a dairy in Dorset Road, Clapham. He built it up until a bigger firm bought him up. Then the United Dairies bought up the firm which had taken him over.

Bill worked for United Dairies for a number of years – 400 customers a day, 3,500 stairs to climb each round. He became district manager – seven shops and 16 rounds: 12 shops, 43 rounds.

Then German troops marched into Poland. Bill’s world crumbled around him again much as it had done 15 years earlier and much as it did for thousands of others.

He returned to a milk round, this time in Kensington. Twice his home was blitzed. Once his wife was buried in the wreckage. Twice blast shattered his windows.

Meanwhile his brother’s son had followed their example in the First World War and joined the Canadian Army. Outside Rome Bill’s nephew won the M.C. for gallantry. He died there.

Back in England fate played another trick on Bill. In the First World War a gun had fallen on him. Shortly after the Second World War a crate of milk fell and split open his stomach. Bill still carries the scars. After that he was not quite so good at lifting things. He had to leave his job.

Just over three years ago Bill got another job – with Associated-Rediffusion.

You’ve probably seen him many times and he’s probably smiled at you and said ‘Good morning’ many times. For Bill, now white-haired, always has a cheery smile, much as he did for housewives on their doorsteps in days gone by.

Bill enjoys life as a labourer in Television House, shifting goods and furniture, restocking toilets with towels, soap and toilet rolls, clearing out wastepaper.

He thinks you all are wonderful people. ‘I do honestly believe that. Everybody is so considerate, patient and tolerant. I’m grateful to all I come in contact with.’

It was nice meeting you, too, Bill Shaw.

But Bill nearly always has a companion on his work around Television House, as most of you will know.

He is another Bill – Bill Farrell. Grey-haired and broad faced, this Bill also enjoys working here. For him, too, life here is quite a contrast to previous days.

Many are the times that his hands have been stained red by the Rowley Red Clay from Staffordshire. For Bill Farrell spent 35 years working for the Royal Doulton Potteries at Lambeth as a plaster model maker and a mould maker.

From his moulds were cast the terra-cotta façades for many of the buildings in London. Thousands of Scotch whisky flagons have also passed through his hands – he helped make them, not drink the contents.

Beer is his drink. During the war he was holding a pint of bitter in the ‘Prince of Wales’, Stockwell, when the place was hit by a bomb. Sixty people were in the pub at the time. Six got out alive. That’s about the only pint of bitter Bill Farrell has never finished.

Another time in the war he was going down to the cellar during a raid when a bomb dropped near by. The cellar door came away in his hands.

But that sort of thing does not happen around Television House these days. ‘It’s a change working here, wandering around the building all day, after 35 years shut up in one room at the pottery.’

Bill Shaw and Bill Farrell may not have the most glamorous of jobs in television but it is interesting to reflect that they are probably one of the best-known pairs of people in Television House.

About the author

'Fusion' was the quarterly staff magazine for Associated-Rediffusion and Rediffusion Television employees.