Profile of John Spencer Wills

A biography of the head of British Electric Traction, the owners of Rediffusion

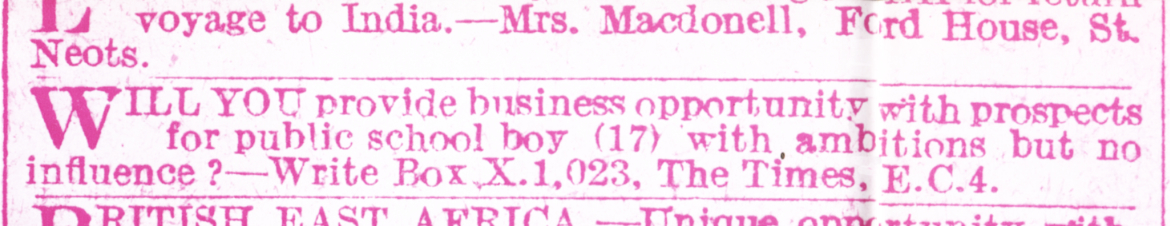

The cutting above is a reproduction of a personal advertisement on page one of The Times on October 10, 1921. The ambitious 17-year-old responsible had carefully picked his words to create the biggest impact from the 15s. [75p in decimal, £30 in today’s money allowing for inflation – Ed] investment in himself.

Today The Times prints – without charge – parts of the speeches made by the leader that youngster has grown into. The shrewd, successful, 55-year-old business and financial expert responsible for those speeches selects the ideas which his judgement tells him will succeed just as carefully as he picked the words for that advertisement. Today, however, the loss could be millions of pounds not 15s.

The advertiser in The Times in 1921 and the man quoted in that paper today is John Spencer Wills, president of the B.E.T. Federation Ltd, deputy chairman and managing director of the British Electric Traction Co. Ltd, chairman of Associated-Rediffusion Ltd, chairman and/or director of various omnibus companies in the B.E.T. group, past president of the Institute of Transport, deputy chairman of the Monotype Corporation Ltd, … an abbreviated list occupies three column inches in Who’s Who.

He did not waste his 15s. in 1921 nor has it been his habit to waste either words or money since then. He has used both to work for him better than most who were born in the early 1900’s.

During the First World War he attended first a preparatory school in Shropshire and then the Merchant Taylors’ School, London. John Spencer Wills played the usual games without distinguishing himself at any of them, although, significantly perhaps, he did like steeple-chasing more than other forms of exercise. He admits that he found rugger a little frightening. No doubt some of his contemporaries who played the game with gay abandon would today find his responsibilities positively petrifying.

The lanky youngster might have continued in this fashion had not fate intervened. He outgrew his heart and was ordered by the doctors to give up games. The academic side of his activities flourished. Mathematics and science were the subjects he enjoyed most and was, therefore, the best at. We shall see that later on in life he was to find another favourite subject – work.

Here at Merchant Taylors’ he came under the influence of the first of two outstanding men who were to make a great impact on his early years. This man was Dr J. A. Nairn, the headmaster at the time. The scholarly authority and penetrating judgement of this doctor of divinity, who had been appointed headmaster at 26, made a lasting impression on the schoolboy. Their friendship did not end when the youngster left school in 1921. Upon Dr Nairn’s retirement five years later the Lord Chancellor (an Old Merchant Taylor incidentally) appointed him to the living of Stubbings, near Maidenhead. There Dr Nairn christened the younger son of John Spencer Wills, 20 years after his pupil left the school.

The year 1921 was not a good one in which to start a career. Jobs were hard to find. People were beginning to talk about The Slump. The tall, slim youth decided to advertise in The Times and thereby established an important principle he has followed throughout his career. He believed that more satisfactory results could be achieved from people approaching him rather than the other wayround. He still does.

And his faith was justified for among the replies was one from a Mr Emile Garcke who wrote, in his own hand, saying he wanted ‘an educated young gentleman with a view to making him my private secretary’. It did not take John Spencer Wills long to find out that Mr Garcke was head of the executive of B.E.T. An interview resulted in the following letter from Mr Garcke:

Ditton House,

Near Maidenhead.

21st October 1921

Dear Sir,

Replying to your letter of 18th inst and call yesterday I write to say that you are appointed to the position of my personal confidential clerk at £50 p.a. [£2,100] payable monthly and in addition, you will have board and residence and washing hill at above address, free also a season ticket between Maidenhead and Paddington. The engagement will be terminable by one month’s notice on either side. When you are in London – about three days a week – you will provide your own luncheon.

I suggest you should commence your duties on November 1st and that if convenient you should go down to Maidenhead on Monday 31st, by train leaving Paddington at 6.33 p.m. I shall be on the same train and a motorcar will meet us at Maidenhead station. I enclose form of application for railway season ticket for you to fill in and return to me. I do not know whether you have a bicycle but you would find one useful as my house is 2 miles from the town.

Yours truly,

E. Garcke.

Fortunately John Spencer Wills did have a bicycle. He also had ambition and courage. Most youngsters would have accepted the offer without more thought than that it might be a useful entry to the B.E.T. But the 17-year-old boy who was about to take his first job was not satisfied with a possibility. He wanted a certainty, and so he made it a condition of his acceptance that he would be taken into the B.E.T. organisation proper after two years. Even before embarking upon his career he had laid down the first of many conditions to follow; already he had his eye on the main chance.

Mr Garcke was the second man to have a very big influence on the rapidly maturing youth. A tireless, painstaking worker, he had founded the B.E.T. empire and was responsible for building it up, company by company. Some of his qualities were undoubtedly passed on to his confidential clerk.

John Spencer Wills lived at Mr Garcke’s home in Maidenhead, travelling up to London most days. Much of his time was spent assisting Mr Garcke in his hobby – philosophy. For hour after hour he pored over books in the London Library, picking out extracts on philosophical subjects. More hard labour went into the compilation of a special file of triads needed for the book Mr Garcke was writing. Today this privately published book, Individual Understanding, is a treasured possession of John Spencer Wills.

But the young clerk acquired more than a knowledge of philosophy from Mr Garcke. He also learnt something about bee-keeping. The old man took it up as part of his philosophical study. And such was Mr Garcke’s ability to grasp a new subject that he was lecturing to the Beekeepers’ Association within a year.

John Spencer Wills learnt how to mount the tongues of bees on slides and how to file Mr Garcke’s investigations under a complicated system of classification of the sciences. He was shown the importance of attention to detail at an early stage in his career.

But possibly more important still was the fact that his position gave him a valuable insight into the work of a man at the peak of his power. This glimpse from the top right at the start must have acted as a considerable spur to his ambition.

Perhaps Mr. Garcke, too, realised that his clerk could not be held back for after one, not two, years, John Spencer Wills was transferred to the B.E.T.’s Secretaries office.

He worked at the headquarters in Kingsway as an assistant secretary to a number of bus companies and lived in the suburbs in a dingy, none-too-comfortable bed-sitting-room at Palmers Green. Such was the start for a man who now lives in a house in Kensington during the week and on his own Sussex farm at the weekends. He recalls those days with an amused shudder.

Already he was making sure that it would not be his lot for long. For two and a half years most of his spare time was occupied in study. He passed the Intermediate and then the Final examination of the Incorporated Secretaries Association (now merged with the Chartered Institute of Secretaries).

Soon he realised that acting as a company secretary was not going to result in quick promotion. So he decided to go into the field; to get a job working in the provinces with one of those bus companies.

At last a chance came; B.E.T. acquired a new company in Hull. John Spencer Wills applied to go there and was appointed its secretary and accountant at a salary of £260 a year [£12,500]. Now he had both a bedroom and a sitting-room in his digs.

But before he took up his new job he was sent to the Eastern Counties Road Car Co. Ltd, for a three-week course of intensive training.

And so he arrived in Hull armed with ambition, drive and a little book full of notes on how to run a bus company. And in Hull he had a big shock. There was no proper office, hardly any staff and not even a reliable ticket system. John Spencer Wills rolled up his sleeves.

The situation might have been designed for him to achieve the greatest possible impact. He created order from the chaos and within a very short time was appointed the company’s general manager. At 22 the young man from headquarters had made a very big mark.

It is difficult to estimate the importance of the effect the next four years had on him. His chairman left him to get on with running the company’s affairs. If he wanted to put up the fares or anything else he did it. For four years he laid a very solid foundation to the company which had become the East Yorkshire Motor Services Ltd. Today he chuckles as he recalls those years. It was great fun for a youngster to have such power.

But the slump had arrived and it was not so much fun to have married men with two or more children coming to him and begging to be taken on as a clerk at 35s. a week [£1.75 in decimal, £90].

Ask him why he stuck with buses and he will become slightly annoyed. In those days there was no chance to wander from pasture to pasture, finding the most tasteful grass. People were delighted to keep what they had got. As a man with the power to hire and fire their plight was brought home to him in no uncertain fashion. He interviewed a steady procession of working men, their elbows sticking out of their coats, their families lacking clothes and food. Despite this he liked bus work.

In Hull it resulted in his being involved in something else which must have had a big effect on the formation of his character. This was a running fight with Hull Corporation who operated a rival bus service.

The young general manager found himself far from the calm, well-mannered, orderliness of the Kingsway headquarters of B.E.T. He had wanted to go out into the field but he had not realised that it would be a battle-field.

He found himself in head-on conflict with the chairman of Hull’s watch committee which was then responsible for licensing bus services in the city. The educated, well-brought-up, man from the South was faced by a self-made stoker, a Socialist by conviction and a blunt, forthright Yorkshireman by birth. Any attempt at reasoned argument was met with a stoker’s sledgehammer vocabulary. John Spencer Wills did the only thing possible – he learnt to talk the same way back.

The only snag was that the watch committee’s chairman was deaf, relying on a hearing box with earphones to listen to the young man’s retorts. The stoker adopted the only effective counter he knew to his opponent’s cogent arguments – he switched the hearing box off.

The watch committee and its chairman soon made up their minds about their attitude to the rival company’s general manager. Without putting it too strongly, they hated his guts.

But already John Spencer Wills had attracted attention from those in London. At the age of 26 he was asked to return and become a director with B.E.T. Five days after he had accepted this invitation, the corporation, not knowing of the move, surrendered. They sent a deputation to ask him to take over the management of the corporation’s bus service. It is interesting to reflect what would have happened had that deputation arrived five days earlier.

Now, however, John Spencer Wills had his feet firmly on the B.E.T. ladder. He describes his progress up that ladder over the next 20-odd years as steady, progressive plodding. This plodding carried him through the chairmanship of more than half the bus companies in the group.

But it did not carry him either so high or so fast as another facet of his earlier life which has more than a little bearing on his character. For six years, from 1933 to 1939, he held a pilot’s licence.

He took up flying when he was 28 for two reasons. First, he wanted to prove to himself that he could do it. Secondly, he thought that B.E.T., with its vast public transport interests, would expand into aviation. Until 1942 he was in fact managing director of British and Foreign Aviation Ltd and chairman of a number of aviation companies. The war, however, knocked things sideways.

He might have been a good pilot but he was a very bad navigator. Once when flying back to London from the cast he became lost and landed in the middle of a housing estate to find out where he was. The only way out was to take off smack between two houses. Today he smiles when recalling the incident and admits that he might have been killed.

More of the dare-devil in his make-up is revealed when he recalls watching the Boat Race by flying round in circles a few hundred feet above it. He also remembers taking up a girl to show her the sights of London from the air. (There was no restriction on low-flying in those days.) She was sick into her handkerchief and tossed it overboard. The slipstream caught it and smacked it back across the pilot’s goggles. John Spencer Wills is probably the only man alive today to have flown blind a couple of hundred feet above London. The girl, grand-daughter of Mr Emile Garcke, is his wife.

That was a lighter incident in his career. A more important event, which demanded just as sure a grip on the controls, was the grim battle over the 1945 Labour Government’s bid to nationalise the bus companies. Already B.E.T. had lost its electricity and gas undertakings to nationalisation. Now it was threatened with the loss of its interest in public transport.

Two big companies – Tillings and the Scottish group – sold out to the Government. But B.E.T. stuck to its belief that nationalisation was against the interests of the public, its stockholders and its staff. The fight was strenuous. Perhaps it reminded John Spencer Wills of his earlier battle against Hull Corporation; perhaps he used some of the techniques he learnt then. Nobody will dispute that he played a very important role in the anti-nationalisation campaign.

It was around this time that he was approached by Mr Allan Miller, then the controller of Broadcast Relay Services (later to become Rediffusion), with offers for him to become the managing director of the company. Each offer was more attractive than its predecessor. Each was refused. Allan Miller was not the sort of man to take ‘no’ for an answer. Nor was John Spencer Wills the sort of man to shift from the position he had taken up. It looked like stalemate but eventually a solution was found. The B.E.T. group, faced with big losses from nationalisation, took over Rediffusion and John Spencer Wills became chairman of it as well as managing director. The belief of John Spencer Wills in people approaching him had again been borne out.

Meanwhile the threat to nationalise buses had been halted so B.E.T. was left with its bus companies and Rediffusion. A few years later it was only natural that Rediffusion, with its television systems in Bermuda and Montreal already operating, should be among those to apply for a contract when it was decided to set up Independent Television in this country.

Once more John Spencer Wills and his fellow directors were called upon to make a coolly calculated decision. After many hours of anxious thought and deliberation, in which he played no small part, the decision was taken. Associated-Rediffusion was formed.

The story of the company’s early days, with the losses growing and growing, is well known. Not so well known arc the talks, worries and decisions which bespattered those troublesome times. Associated Newspapers withdrew. B.E.T. and Rediffusion took over their interests.

Behind it all were men who had considered every factor and decided to stick it out. John Spencer Wills carried more than his share of the responsibility and worry.

Now Associated-Rediffusion is under attack for the amount of money it makes and some of the programmes it transmits. As chairman he has little time for these attacks. He is not ashamed of making a profit nor is he ashamed of the programmes transmitted. But he does get annoyed at what he describes as ‘high falutin’, carping criticism’.

He thinks that the desire for entertainment and escapism are not far separated and he is not afraid to admit that, in common with a great many other people, he likes Westerns. John Spencer Wills makes no bones about the fact that he is proud to be chairman of Associated-Rediffusion and has been heard to describe the staff at Television House and Wembley as ‘a damn good lot’.

He genuinely believes in alternative and not competitive programmes. While admitting that this would be in Associated-Rediffusion’s interest, he is convinced that it would also be in the interest of the public to have a real, alternative television service.

He is also adamant about the value of people talking things over round a table. John Spencer Wills does not aim to set himself up (or anybody else) as a dictator in Associated-Rediffusion or any other company. ‘We’ve not got any and we certainly are not going to have any either.’

His own policy is not to interfere unnecessarily. He describes his role at B.E.T. as that of ‘Cabinet maker’ – to appoint the chairman and directors of the many companies within the group.

Many characteristics have combined to help carry him up the B.E.T. ladder. You will have gained a good idea of some of them from the preceding pages.

Mr W. T. James, who has also climbed high in the B.E.T. organisation, has known and worked with him for 27 years. He sums these characteristics up as follows:

A tremendous capacity for work, backed by a keen, perceptive brain. A forceful, analytical mind, logical in argument and quick to find a weakness in a case or document. This makes him a tough man with whom to negotiate. A virile imagination takes him a jump ahead of most people. He has the ability to issue the right orders and to make sure they are carried out. While not tolerating fools gladly he is a fair-minded, not ruthless, man.

Today John Spencer Wills has a not inconsiderable private fortune. Like others in a similar position he would be much better off financially if he avoided our high taxation and went to live in Bermuda or the West Indies. Why doesn’t he? Ask him and you will get a simple answer which also accounts for a great deal of his success. ‘I enjoy my work.’

Much as he attributes his success simply to this enjoyment of his work, so his chief hobby is simple. It is complete idleness. Walking and shooting are other occupations. Most weekends will find him out walking around the 2,000 acres, largely woodland, he owns in Sussex. Each weekday he compromises by walking from his house, through Kensington Gardens, to his office at Stratton House.

Dairy farming interests him as well. He lives on one farm near Battle and lets another five farms to tenants. He enjoys novels, good or bad, and likes to go to the theatre to see a serious drama.

Happily married to a lady who is well-known in the B.E.T. organisation for her charm and frequent attendance at functions all over the country, he has two sons. Colin, aged 22, is articled to a chartered accountant. Nicholas, aged 18, is now in Australia acting as a jackaroo on a sheep station before going up to Cambridge in October.

John Spencer Wills has no need to use the advertisement columns of The Times today. If he did he would certainly require more than the 17 words in which he described his qualifications in 1921. Then he had ambitions but no influence. Today he has achieved many of his objectives and acquired a lot of influence in the process. But the impression remains that he has some ambitions still to fulfil.

Sir John Spencer Wills (10 August 1904–28 October 1991) was chairman of Associated-Rediffusion.

About the author

Ronald Elliott was editor of 'Fusion', the Associated-Rediffusion house magazine, and wrote and edited for A-R's subsidiary TV Publications Limited.