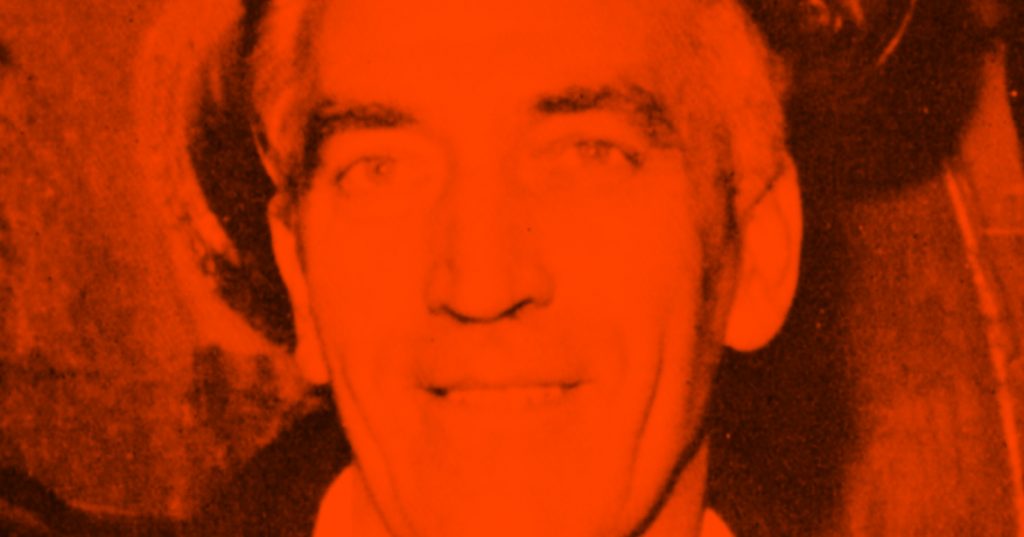

The man who keeps Wembley warm

Meet Jack Elkins, in charge of the boiler room at Wembley

At first sight it would appear to be impossible to connect a death at Broadcasting House, fires in a yard on which Studio 5 now stands, the battle of El Wisket Ridge, two fair-sized boilers and some pumps in Studio 1 at Wembley.

The clue as to how all these things can be linked lies in the name of Jack Elkins who has been making things connect at Wembley ever since 1934, apart from the war years when he was himself connected – to the Army.

Jack Elkins was born in Wales 44 years ago this month (October). George Elkins, his father, came from Nottingham and had gone to Wales to work in a power station at a mine. His mother was a Londoner.

Perhaps that is why his parents decided to move to London when the slump hit the Welsh coal mines in 1928. Jack and his three brothers, moved into a new home where the back gate led out onto fields. They were brought up within reach of the fresh, green countryside. The house was in Kenton and Jack Elkins and his wife still live there but his three children have farther to go for the countryside. As Jack grew up so did the houses – all around them.

Back in 1928 Jack’s father found work at what were then the Wembley film studios on the site now occupied by our studios. One by one the sons left school and one by one they, too, found work at Wembley. Jack was the youngest of the family and the time arrived when he, not unnaturally, joined his father and brothers there as well.

One by one the Elkins have left Wembley. Jack’s father retired from the boiler-room in 1947. He died a few years ago at the age of 82. Fred, who was an electrician at Wembley, is now a lighting charge-hand at the Merton Park film studios. Four years ago Bert also left his job as a set storekeeper to join a film studio. Today he is a camera grip operator at Ealing. Finally, two years ago Alf left the boiler room to work in another boiler house belonging to H.M. Stationery Office.

Only Jack remains, constantly to pop up in all parts of the premises where his job as charge-hand plant supervisor carries him. But back in 1934, when he first arrived, his job only carried him as far as the banks of glass batteries used for the sound equipment – six columns with four dozen batteries in each column.

This is where the first of the apparently unrelated items in the opening paragraph of this article comes into the picture – literally. For ‘A Death at Broadcasting House’ is the film which Jack Elkins remembers most from those early days. The cast included an actor by the name of Val Gielgud.

Wembley belonged to Associated Sound Films when Jack Elkins first arrived. Then it was acquired by British Talking Pictures who developed into Twentieth Century Fox. They used the studios to turn out quota pictures – one, or more, a month.

‘We were kept pretty busy’, says Jack in a characteristic understatement. ‘The interesting thing about those days was the fact that when we arrived in the morning we never knew when we were going home – that day or the next.’

Another interesting feature was the colossal waste of timber. They had an excellent system for clearing a studio of sets at the end of filming. Quick as it undoubtedly was, this method would hardly be considered today despite its attractive, basic simplicity. The idea was for a man to go round with a hammer and knock the supports away from the scenery. (Perhaps this was how the term ‘strike sets’ was derived?) Anyway the result was that the sets crashed down in a twinkling.

The method of disposal after this was also remarkably simple. The shattered remnants were piled up in the yard on which Studio 5 now stands and when the heap became unmanageable it was set on fire. Think of the amount of storage space which could be saved if the same system was adopted today.

Back in 1939, however, another sort of fire blazed up. Jack Elkins left Wembley to join the Rifle Brigade, serving in North Africa with the 9th and 2nd Battalions. ‘We went backwards and forwards across the Western Desert a couple of times’, is his phlegmatic summing up of the war out there. Tobruk, he recalls, was ‘a bit of a shambles’ when he last saw it.

It also appears that life was ’pretty warm’ when his battalion became involved in the Battle of El Wisket Ridge. ‘The infantry took the ridge. Then we were placed up there with anti-tank guns, blankets, ammunition and food. The idea was that we should hold it for three days.’

But they only stayed one day. During it the German tanks attacked continuously despite the fact that 50-55 of them were put out of action by the anti-tank guns. During that day also, his group used up all the ammunition which was supposed to last for three days. At the end of it they were told to disable their guns and make their own way back.

An indication of how ‘warm’ it was can be gathered from the fact that the battalion’s colonel was awarded the V.C.

Back at base Jack Elkins was asked if he could ride a horse. Upon giving a negative reply he was transferred to the Mounted Military Police.

For his remaining 18 months in North Africa Jack Elkins and his horse patrolled army food and lorry dumps. Then, in 1945, after four-and-a-half years out there, he was shipped home and demobbed. Back he went to the boilerhouse at Wembley.

The Wembley studios had meanwhile been doing their bit to win the war by turning out training and other films for the Army Kinema Unit. They, too, were demobbed back into the hands of Twentieth Century Fox and were let out to different film makers in the next few years.

Then, five years ago last January, Jack Elkins, his boilers and the studios were taken over by Associated-Rediffusion. Jack Elkins and the studios (with the addition of grey hair to the former and sundry alterations to the latter) are still with us but the old boilers have gone.

They had been working ever since 1929 (when what are now Studios 1 and 2 were being constructed) and Jack Elkins had been making them function for a good proportion of that time. Two years ago they were replaced by two smooth, shining, almost silent, new boilers. Each one measures 10 ft. by 7 ft. and each has an evaporation of 4,000 steam pounds per hour to provide heat for the radiators and hot water for the buildings. When it is really cold in the winter they have to be fed with 2,700 gallons of fuel a week. In the summer they tick over happily on 200 gallons a week.

‘I wasn’t sorry to see the old ones go. They gave a little bit of trouble occasionally’, says Jack with a slight smile which left the impression that the trouble was more than slight on more than one occasion but that Jack Elkins was equal to his boilers.

There was one day, however, when he was almost beaten – before the new boilers were installed. As he was approaching the boiler-house he heard what sounded like a terrific explosion. He rushed into the building expecting smoke and fury. He was wrong. A hurried inspection revealed that all was apparently well. It was – until they started pumping up oil into the gravity feed tank. The ‘oil’ turned out to be water which had seeped through to the tank under the floor and in through a burst pump connection. The explosion he had heard was the sound of the tank leaving its base and hitting the floor.

That’s about the only time Jack Elkins has come near to hitting the roof – either literally or metaphorically. Normally everything is spick and span as it should be with the man who is also responsible for the eight women day-cleaners, the five male night-cleaners, the one toilet cleaner and one general labourer who come under his domain, not forgetting the two plant attendants who assist him in the boiler-room and around the building on any plumbing job which might turn up. These jobs can vary from alterations to equipment to finding wedding rings down a sink. They also include the ‘practicals’ on a production such as laying on gas or water.

‘They come in cycles. During the summer people mostly seem to want rain, and in winter they want fires and cooking facilities’, says a man who is obviously accustomed to every sort of strange request.

And that brings us to the last of the items in the list in the first paragraph.

‘Excuse me Jack, they say they need some pumps in Studio 1’, says a visitor to the boiler-house.

‘Left it a bit late haven’t they’, says Jack. ‘All right, I’11 come and have a look’.

They got their pumps but then if Jack Elkins has anything to do with it they generally do get what they want.

About the author

Ronald Elliott was editor of 'Fusion', the Associated-Rediffusion house magazine, and wrote and edited for A-R's subsidiary TV Publications Limited.