Oom-pah-PAH and Joanna

Backstage at the Royal Festival Hall in 1963

Associated-Rediffusion gives financial support to both the Halle and the London Symphony Orchestra. Everybody knows the high standards reached in public concerts. But how is this achieved? What goes on behind the scenes at a rehearsal? Fusion asked sally sutherland to report on a rehearsal at the Festival Hall and patrick ward to capture the atmosphere in photographs…

Associated-Rediffusion has made several brave attempts to find a successful technique for putting a symphony concert on the television screen, but so far has not succeeded to its satisfaction. The best attempt I remember was Cyril Coke’s in which he devoted the first half to the rehearsal and the second to the actual performance of Stravinsky’s ‘The Firebird’ by the Hallé. I remember this as an interesting and rewarding experience and by being intrigued by the musicians’ transformation from slacks and sweaters to their soup and fish.

It was with this memory in mind that I eagerly accepted an invitation to visit the Royal Festival Hall for the London Symphony Orchestra’s final rehearsal for the night’s concert.

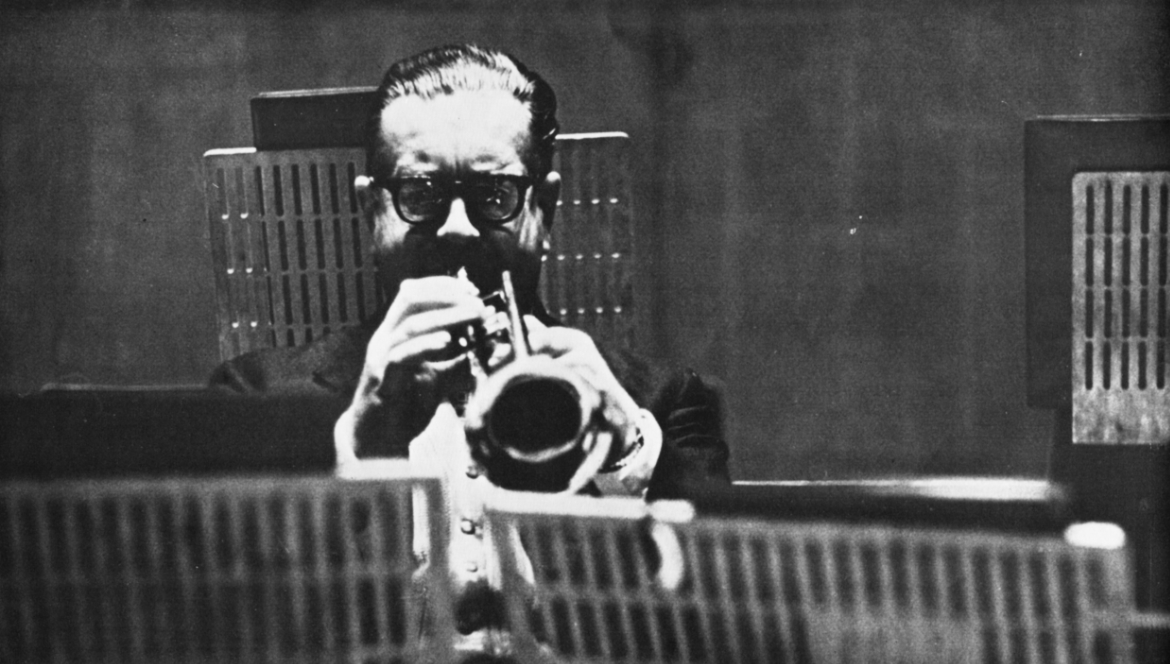

The vast auditorium, dark, hushed in a reverent silence, contained only a handful of shadowy figures as I crept in and oozed into a seat. The stage, brilliantly lit, seemed filled by the orchestra which was already at work. The conductor, I knew, was Pierre Monteux. Short, stocky in a workmanlike grey cotton jacket, with his dark curling hair and surprising white walrus moustache, he is the principal conductor of the L.S.O. He is acknowledged, moreover, as the doyen of all conductors, being in his 88th year. Despite his age and long years with the baton, he seemed as vigorous and fiery as any young man. There is a story that when he was offered a contract with the L.S.O. in 1961 he insisted it should be a long-term one and I believe it lasts until he is 100!

Ignoring the score, Monteux, his small expressive hands gently coaxing, began guiding the orchestra through what I thought I recognised as Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’. This work had obviously been well rehearsed before with the result that only short bursts of it were played. ‘The last ten bars again, please.’ All too soon Monteux closed the score at which he had only looked to count the bars and that was that.

In the pause that followed, I realised with a jerk that I was not going to sit there and enjoy a jolly free concert. In fact, I was not going to hear a work from beginning to end. The orchestra, being composed of individual virtuosos who can read a score at sight, was only there to give the programme its final finishing touches and subtleties as required by the conductor. Nevertheless, it would be fascinating to be behind the scenes as it were.

While a shuffling of scores went on 1 gazed round at the other listeners. Two earnest young men sat, one in front of me and one way at the back, with score on lap and ballpoints at the ready. A young woman sat on the edge of her seat, her hands clasped as if in supplication beneath her chin – very intense. Behind me I saw a small girl all in blue. Blue jersey, blue skirt, blue tights and legs that stuck out straight before her, her sandalled feet turned up. As she sucked what appeared to be an ice lolly, I saw an open violin case beside her. One did not need an A level G.C.E. to guess her Dad was in the orchestra. She sat quietly, her round blue eyes fixed on the stage.

The student in front of me (an American incidentally) kindly gave me the concert items. It was not the ‘Eroica’, but I felt a bit smug to find that it was Beethoven’s ‘The Creatures of Prometheus’ from which the composer had lifted the theme for the last movement of the ‘Eroica’. To follow was the Brahms Symphony No. 2 in D.

Now Monteux tapped his baton and every bow was at the ready. I was looking forward to the Brahms and my thoughts wandered to a terrace in Sussex where I had last heard it on an appropriately hot afternoon. But in no time came that tap-tap again. Monteux, who had been leaning over the violins, swung round to the cellos behind him. He had heard a wrong note through the back of his head.

‘Non, Non,’ he said, ‘B naturelie! It goes oom-pah-pah-paah.’

Thus singing he led the players into the Allegretto. In fact he sang for the greater part of the rehearsal. Occasionally he varied OOM-Pah-PAH with Ta-Ta-Te-TEE. At one point he emphasised the singing tone of the violins by laying his baton across his left arm as though playing the instrument himself. Come to think of it, this was not so odd since he was a violinist at the age of six before becoming a conductor at 12.

The beauty of the fragments so far played of what is sometimes referred to as Brahms’ ‘Pastoral’, had soothed me into a trance. All too soon the soft, high trumpet notes of the first movement returned to warn us that the finale was at hand. And that was that.

The L.S.O. now prepared for the pièce de resistance, Berlioz’s ‘Symphonic Fantastique’. There was much tuning of strings and a viola player carefully laid a clean square-folded handkerchief under his chin. As Monteux raised his baton the concentration was so intense it was almost concrete. You could have leaned on it.

A Largo, sad and gentle, proclaimed the theme and we listeners sat back to be moved and excited by this masterpiece. Phenomenal that Berlioz, was only 27 when he composed it and only nine years before had never heard any music other than his local folk melodies. The story in the Symphony of a young musician who, in despair due to unrequited love, takes to opium, ends on the scaffold and descends to the torments of Hell, is musically something to make your spine chill and tingle. It is, I later learned, one of the works most dear to Monteux, whose understanding of his compatriot composer is said to be unrivalled.

Behind me, the small girl had now peeled a banana and was nibbling the fruit while the starfish of its skin hung round her hand.

Monteux made short work of the first movement. With a shower of chromatics, shimmering sweeps on the harp, and sustained soarings of the violins, we sped into the waltz. This, too, ended all too soon. The cor anglais began its melancholy solo starting the third movement and then was echoed by an oboe off stage.

Monteux tapped for silence and the oboeist popped his head surprisingly round a curtain at the side of the auditorium close by the stage.

‘A leetle louder, please’ said Monteux. ‘The pooblic here (sweeping his arm over the auditorium) will not hear you so far away. Come a leetle closer (the oboeist moved until he was a bulge in the curtain) and now louder – ta-ta-ta-tee-TEE.’

Beautiful as the third movement is, I was impatient for the poignant March to the Scaffold. Inevitably one waits for the crash of the orchestra as it brings down the guillotine and snaps off the theme played so wistfully on the clarinet. I was not to hear it. There was a light touch on my arm.

‘Would you take me to the toilet, please?’ asked the small girl in blue.

Hand in hand we climbed the long flight of stall’s and, thank heaven, in the lobby outside found the ‘Ladies’. She assured me she could manage by herself and all was achieved satisfactorily.

Now that I saw her in the light I realised what an attractive child she was. Her fair but not golden hair waved to her head like a helmet and her eyes were of a striking blue.

‘What’s your name and how old are you?’

I enquired.

‘I’m Joanna and I’m five. What’s your name and how old are you?’

‘I’m Sally,’ I replied nothing daunted, ‘and I’m ninety’.

‘Oh,’ she answered in complete acceptance. We started back to our seats and on the way I learned that her Daddy was in the orchestra; she had a little sister called Tina; she was learning the piano; she often came to rehearsals but never to the concert at night; and wasn’t it a pity I had no little girls or boys of my own.

Joanna returned to her seat and busied herself with paper and pencil.

By this time Monteux and the L.S.O. were going hammer and tongs at the ‘Nightmare of the Witches’ Sabbath’. In the midst of a really menacing section the conductor stopped.

‘A leetle more on the snarl, please. Anngrrrr’ he illustrated with gritted teeth and the orchestra laughed. ‘He is among the beasts now. Better you should be too loud than no one should hear you. Again.’

Now a trombone (I think) tore off a series of snarls so fierce as to frighten the wits out of anyone. The finale got into its stride with trumpets braying, fiddles ‘sawing away regardless’, the drums and timpani going double forte and everyone doing his utmost to a tempestuous finish.

It was all over. Spectators and players burst into applause, shouting ‘bravo’ to the conductor. He modestly bowed and thanked the gentlemen of the orchestra.

As I was about to leave, there was another touch on my arm. I turned to meet the orchestra leader, Erich Gruenberg, in his gay red pullover.

“Thank you for taking care of my little girl’ he said.

‘It was a pleasure’ I answered. ‘She is very charming.’

‘I know. That is perhaps why I was a bit alarmed when I saw you take her out of the hall.’

‘You saw? In the middle of the Symphony?’ I was astounded. I couldn’t believe that anything could have broken that concentration.

‘Oh yes. However I didn’t worry. The bass player gave me a sign that it was all right.’ The bass player too. Evidently he knew Joanna’s shortcomings better than her father. As a matter of fact, I shouldn’t be surprised to learn that all 80 members of the L.S.O. witnessed my exit with Joanna.

She now approached me with two pieces of paper.

‘Look’, she said, ‘I did these for you’.

I thanked her and admired some youthful drawings and a sheet of writing that told me the numbers from 1 to 20 and that each member of her family by name was OUT.

I left the Royal Festival Hall wishing with all my heart that somehow someone could find the formula that would bring these fine players and the enjoyment I had experienced to our millions of viewers.

About the author

Sally Sutherland was Programme Publicity Officer at A-R